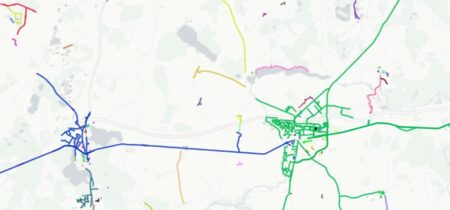

Mixed traffic

Cyclists can cycle in mixed traffic, but various types of speed regulation may be necessary. Good solutions for bus stops and parked cars are also necessary to keep them from becoming obstacles to cyclists.

By Troels Andersen

Cyclists often feel insecure in mixed traffic, especially when the traffic is heavy and moving fast, and there are many lorries. The safety level depends on the rate of speed, parking facilities, and road width, among other things. Consequently bicycles and cars should only be mixed on stretches where there isn’t much motor traffic, and the speed limit is suitably low.

- It’s a good idea to reduce speeds here, with speed bumps, for example.

Six out of ten cyclists experience conflict situations in mixed traffic. On roads with cycle tracks only one third of cyclists experience conflict situations. The most frequent types of conflict situation for cyclists in mixed traffic are other road users’ behavior, parked cars, and intersections, whereas on roads with cycle tracks the main problems occur at intersections and side streets.

Cross profile

According to an American study, traffic lane width is not a significant factor for the cyclist’s experience of the road in urban areas. Danish studies support this.

The width of an urban road has either little or no significance for cyclist safety, but cyclist risk in open country drops when traffic lane width is increased.

- Speed bumps are an extremely effective traffic calming measure. The bump can be installed across the full width of the road without a cycle shunt, which is best for cyclists, and cheaper to establish. Photo: Troels Andersen

When road widths are less than 6.5m in urban areas, the speed limit for motor traffic should not exceed 30 or 40 km/h. If the speed limit is higher, the traffic lanes should be wider. At speeds of over 40 km/h planners should consider traffic calming or segregating cyclists from motor traffic.

On roads where cars drive 30-50 km/ h and often pass cyclists at the same time as cars coming from the opposite direction pass by, the choice should be whether to segregate cyclists from cars or mix cyclists and cars in a wide traffic lane, depending on traffic volumes, parking facilities and available space. The presence of large numbers of children and older cyclists is another important parameter that speaks in favour of cycle tracks.

Parking

Cyclists in mixed traffic often experience parked cars as a problem, and the cyclist accident risk in mixed traffic is increased by the presence of parking bays and bus stops. Parking maneuvers and opening car doors can injure passing cyclists. Scattered parking along the road can make the cyclist less visible to other road users. Either parking should occur in a parking lane or the speed limit should be reduced to 30km/h. When there is angled or perpendicular parking the speed limit should only be 10-20 km/h. Drivers backing up can simply not see small children on bicycles.

- This is bound to go wrong. Parallel parking is what should be installed here. Photo Troels Andersen

The number of accidents drops by 20 – 25% when parking is prohibited even though no parking may mean cars can drive faster. However, no parking can change the traffic pattern and may cause accidents elsewhere.

When parking is only allowed on one side of the rode the risk of accident is greater than on both sides of the road due to dangerous parking maneuvers and uneven fields of vision. Nevertheless it may be necessary to only allow parking on one side of the road in order to make space for a cycle track. Another alternative is to place parking on alternate sides of the road.

Bus stops

Collision accidents between cyclists and cars are prevented by bus bulbs in mixed traffic. The cyclist doesn’t have to turn and look behind him for cars in order to pass the bus. As a general rule cyclists rarely look behind them.

In streets with considerable parking, parking and stopping can be prohibited and the bus stop canbe additionally provided with a traffic island. In mixed traffic widening the pavement at bus stops is often an obstacle to cyclists.

- In order to prevent squeezing accidents, the cycle track was established with a traffic island.

Signed speed limit reduction

Planners should consider whether the local speed limit can be reduced by signage. Generally speaking, a speed limit reduction of 10 km/h reduces the actual average speed by 2.5 km/h. In other words, if a 60/km/h speed limit is reduced to 40 km/h an actual speed reduction of 5 km/h may be expected, which is the equivalent of a 10% reduction and consequently 19% fewer personal injury accidents.

In Norway an electronic speed limit reduction around 9 schools resulted in an actual speed reduction of 2 – 11 km/h.

Driver feedback signs

Electronic driver feedback signs can be used where there are many speed limit violations, and are common near schools. Driver feedback signs can be either permanent or mobile equipment.

Radar speed signs result in a speed reduction, and the speed reduction is permanent. In urban areas driver feedback signs result in an average speed reduction of 2-10 km/h. The reduction depends on the speed level and the speed limit in force before the sign came up. The greater the speed violation prior to the sign, the greater the subsequent speed reduction. The average reduction is 5 km/h.

According to a Danish study the effect of driver feedback signs at the town entrance is that the number of personal injury accidents drops by 30%.

Traffic calming measures

Physical traffic calming measures are often necessary in mixed traffic in order to enhance traffic safety and security for cyclists and other vulnerable road users. When the lane shifts or narrows, bicycle traffic needs its own autonomous area: a cycle shunt, track, or lane.

- A good cycle shunt is 1.4 m wide. If the shunt is too narrow some cyclists use the traffic lane, and if it’s too wide cars enter the cycle shunt. It’s a good idea to use beveled kerbs. Photo Troels Andersen

Cyclists feel more secure passing lane shifts and narrowings with a cycle shunt than without one. It’s important to keep 10-15 meters free of parking before and after the cycle shunt, for example by using traffic islands or 20-40 m long cycle lanes. The cycle shunt should be wide enough for a legal bicycle (i.e. at least 1.4 m wide). Parking control is necessary to ensure that cars don’t park illegally in the cycle lane.

Traffic calming and speed reduction result in an increase of pedestrian and bicycle traffic, especially among children and the elderly.

- Pavement widening and planting keep parking under control. Photo: Troels Andersen

A British study of 72 traffic calmed areas showed a reduction of more than 60% in the number of accidents. The reduction was greatest for cars and pedestrians and lowest for cyclists. The average speed of motor vehicles dropped from 40 km/h prior to traffic calming to 26 km/h subsequently. Traffic calming measures don’t have the same positive effect for cyclists as for other road users, partly because most cycling accidents occur at intersections. In Denmark the total safety effect is typically 30%, but only approx. 10% for cyclists.

Sources

Engel, Ulla og Iversen, Lis (1979): Cyklisterskriterier for rutevalg, Rådet for trafiksikkerhedsforskning,Danmark.

Landis, Bruce W.; Vattikuti, Venkat R. og Brannick, Michael T. (1996): Real-Time Human Perceptions– Toward a Bicycle Level of Service, TransportationResearch Record 1578, USA.

Greibe, Poul og Hemdorff, Stig (1998): Uheldsmodel for bygader – Del 2: Model for strækninger,Notat 59, Vejdirektoratet, Danmark.

Møller, Jes og Larsen. Flemming (1983): Cykel- og knallertulykker i landområder – Dokumentationsrapport, Vejdirektoratet, Danmark.

Vejdirektoratet (1992): Cykelstier i Frederiksborg Amt – En brugerundersøgelse, Danmark.

Møller, Jes og Larsen. Flemming (1983): Cykel- og knallertulykker i landområder – Dokumentationsrapport, Vejdirektoratet, Danmark.

Davies, D.G.; Ryley, T.J.; Rayler, S.B. og Halliday, M.E. (1997): Cyclists at road narrowings, Report 241, Transport Research Laboratory, England.

Vejdirektoratet (1985): Trafiksanering af store bygader – nogle eksempler, Danmark.

Taylor, David (1996): The Feet First Report, England.

Taylor, David C. og Mackie, Archie M. (1996): Review of traffic calming schemes in 20 mph zones, Report 215, Transport Research Laboratory,England.

Søren Underlien Jensen – Trafitec: Sikkerhedseffekter af trafiksanering og signalregulering i København Teknik og Miljø, januar 2009.

Trafikksikkerhetshåndboken, Transportøkonomisk institutt