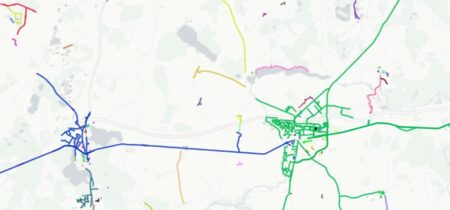

One-way cycle tracks

One-way cycle tracks are the best standard solution for cyclists. They can be designed in many different ways. However, width is the crucial factor and here there must be no compromise. Physical segregation can be constructed in a number of ways, but the Danish kerb is the answer to most needs.

By Troels Andersen, Odense Municipality

One-way cycle tracks should be established along roads with large traffic volumes and/or high speeds. The standard Danish solution is designed so the cyclist area runs on a level between the traffic lane level and the pavement level.

- “The Danish cycle track” with a kerb provides excellent segregation between road users. Photo Troels Andersen

Choice of cycle track type and width should not only depend on criteria such as traffic safety and the budget, but also accessibility, security, comfort, and points of interest. Cycle tracks reduce the number of accidents between cyclists and cars on road stretches. When the dimensioned speed is over 50 km/h, cycle tracks play a role in reducing serious cycling accidents.

There are four main types of one-way cycle track along the road with different costs, space needs, drainage, and experienced service levels. The safety effect in open country is greater on wide cycle tracks. The number of cyclist accidents is reduced by half when cycle tracks are established along main roads in rural areas, whereas the effect in urban areas depends on motor traffic volume, among other things. The more cars there are, the greater the effect. A Copenhagen study showed that cycle tracks increase the number of accidents by 10%, but this figure covers a drop on road stretches and an increase at intersections. During the same period, bicycle traffic volume increased by 20% and car traffic dropped by 10%. Consequently the risk to the individual cyclist is lower.

Cycle tracks apparently have a modest traffic calming effect on cyclists and drivers. In cities, the establishment of a cycle track may be used as a starting point for creating narrower road profiles, better crossing options, etc., and may consequently have a broader safety effect. The estimated reduction in driving speeds is one to five kilometers per hour, depending on traffic lane width and whether the number of traffic lanes has been reduced.

- Safe pedestrian crossing across the cycle track. Photo: Troels Andersen

Cyclists ride approx. 1- 2 km/h more slowly on cycle tracks than in mixed traffic. This is partly because cyclists feel more secure and so they slow down, and partly because they have less space to maneuver and are thus traffic calmed. Cyclists prefer cycle tracks along the road (or cycle tracks with their own layout) that are well lit and have an even surface. The main causes of a negative cycling experience are uneven surfaces, manholes, gully grates, confusing crossings, narrow track profile, and poorly designed bus stops.

A Danish and a non-Danish study have each shown that cyclists experience a higher service level

on cycle tracks compared to cycle lanes. Counts before and after the establishment of a 25 km long cycle track along 10 Danish main roads showed a 37% increase in the number of cyclists on certain roads.

- Trees placed between the cycle track and the pavement are an excellent idea.

Cross profile

The guideline width for one-way cycle tracks segregated from the traffic lane with a kerb, a median strip or a ridge is 2.2 m in cities as well as in rural areas with a guideline minimum width of 1.7 m. In practice, however, you should never go under 2 m.

The guideline width for a cycle track that is part of a separate space system is 1.7 m and the guideline minimum width is 1.5 m.

Studies show that cyclist accident risk drops as cycle track width increases in both urban and rural areas, and in rural areas as verge width increases on main roads.

A cycle track width of 2.2 m enables cyclists to pass safely. Since cycling speed varies greatly from individual to individual, cyclists often pass each other. When there are large numbers of cyclists it may be necessary to have enough space for three cyclists to pass side by side, and a width of at least 2.8 m, preferably 3.0 m.

Wide cross profiles are especially indicated in areas where there are many cargo bikes and bicycle trailers.

- A cycle track with a verge is excellent on main roads and road stretches without side roads. Photo Troels Andersen

Verges

A verge between the cycle track and the road is a good solution on roads with high speeds and few intersections per km of road. Verges are used primarily in the country, and make kerbs and road drainage systems unnecessary. In cities verges should be avoided on roads with frequent intersections.

Grass verges along the traffic lane are assessed positively by cyclists as they provide security and comfort. Danish experience shows that verges do not have a positive effect on experienced service levels until motor traffic speeds reach 60 km. A kerb between the verge and the traffic lane is effective on urban roads to prevent parking on the verge and to improve drainage conditions.

The verge width is established on the basis of a total assessment of planting, visibility, distance requirements to immovable objects, and space. In rural areas a 1.5 m verge is the norm whereas the width varies in urban areas. In rural areas immovable objects such as trees may not be placed on the verge due to driver safety in case of collision.

- The verge should be shortened well in advance of an intersection in order to make cyclists visible. In other words, this is not the way to do it. Photo: Troels Andersen

In cities, verges with trees between the cycle track and the traffic lane should be min. 2 m wide. Trees between the pavement and the cycle track can be planted in a 1-1.5 m wide verge. A grass verge should be at least 0.6 m wide.

Guard rails are usually installed on the hard shoulder since placement between the traffic lane and the cycle track would make a wider verge necessary as well as making mowing and snow clearance more difficult and more expensive. Furthermore, if there are guard rails on the verge it cannot function as an emergency lane.

The same recommendations apply to the placement of noise screens.

- When there are few pedestrians and cyclists a separate space track can work. Or as here, where pedestrians and cyclists have to put up with the remaining space. Photo: Troels Andersen.

Separate space cycle tracks

Separate space cycle tracks, where a cycle path is divided into a pedestrian area and a cyclist area, is established where there are few cyclists and pedestrians and not much space. However, when the cycle track and the pavement are on the same level only separated by markings or different types of surface, the risk of accident between cyclists and pedestrians is increased. Pedestrians tend more or less unconsciously to gravitate toward the cycling area if the marking or the different surface doesn’t clearly show who belongs where. Cyclists tend to cycle on the pavement area if the cycle track is too narrow. An alternative to a separate space is a shared space.

- In spite of the different surfaces, separate space can be a problem when pedestrians and cyclists are there at the same time.

- Ridges can work on roads with very few crossing pedestrians. They are cheap and don’t require changed road drainage.

Ridges

The choice of a ridge instead of a kerb may be necessary for economic reasons. The basic idea of a ridged track is to save costs on drainage and kerbs without losing the advantages of a cycle track. Cyclists generally feel somewhat more secure on ridged tracks than in mixed traffic. Road user experience of ridges can be negative if the ridges aren’t clearly visible. Crossing pedestrians often trip over the ridges.

Ridges are available in different shapes and materials including rubber, plastic, concrete, asphalt and stone. The ridge can be made visible by starting out as a median strip at an intersection. Edge lines and different surfaces can mark the ridge on road stretches. At driveways and exits concrete, asphalt and kerb ridges should have ramps. Other types of ridges should be shortened.

Deformation issues and the like may also arise as a consequence of wheel pressure from lorries and busses.

Road drainage usually occurs through min. 30 cm wide holes in the ridge. No information is available about whether ridges have any effect on the number of cyclists.

Ridges should not be used where large numbers of pedestrians cross the road. Ridges just like kerbs should be approx. 10 cm high in order to provide good segregation from the traffic lane. Ridges are problematic during winter maintenance since they are damaged when driven on.

Possible future scenarios include creative solutions where lights are placed in ridges, for example as running lights.

- The area between pedestrians and cyclists is simply separated by bollards here. Photo: Troels Andersen

Other types of physical segregation

There are also other types of physical segregation, for example bollards. It’s important that bollards are placed 30 cm closer to the pedestrian area than where a kerb would have been placed so bike baskets and pedals don’t get stuck in the bollard.

- The median island between the cycle track and the traffic lane helps pedestrians cross the cycle track and the road more safely. Photo: Troels Andersen

Standard cycle track

The kerb rise towards the traffic lane on a free stretch must be at least 7 and at most 12 cm. The rise on stretches between the cycle track and the pavement should be at least 5 and at most 9 cm. The given guidelines provide the following benefits:

- Most drivers refrain from parking on the cycle track.

- Cars enter and exit buildings and other areas slowly.

- The drainage system functions well.

- Cyclists rarely use the pavement and pedestrians understand that they are leaving the pavement.

The guideline figures are established by weighing benefits against disadvantages, for example, the risk of cyclist and pedestrian falling accidents against the mobility needs of the physically disabled.

- Ramps at crossings often jut 30 cm into the cycle track thereby effectively reducing track width. Asphalt ramps can be reduced by beveling the kerb. Photo: Troels Andersen

Drainage takes place through gullies on the traffic lane and the cycle track. To avoid having gullies on the cycle track, the entire road bed needs to be lowered. Since cyclists usually keep a safe distance from the kerb, gully grates only narrow the used portion of the cycle track to a limited extent.

However, depressions around the gully grates are an issue.

If there is a cross fall towards the pavement, side entry gullies may be installed, and don’t take up space on the cycle track surface. This is especially important when the cycle track is very narrow.

- Parking occurs even though it’s prohibited. Photo: Troels Andersen

Car parking

It’s prohibited for cars to stop or park on cycle tracks. When cycle tracks are established there is a significant drop in the number of accidents between cyclists and parked cars.

On stretches where many vehicles stop or park, a median island along the length of the traffic/parking lane with a width of 1.0 meters can be installed.

There doesn’t have to be a kerb elevation between the median strip and the cycle track. The strip should have another surface than the cycle track. Another alternative is making the cycle track 1 m wider.

- Cars on the cycle track. Photo: Troels Andersen

On roads with parked cars outside the cycle track, a traffic island between the cycle track and the traffic lane at pedestrian crossings can improve pedestrian traffic safety and encourage pedestrians not to stand on the cycle track. Another possibility is to remove some parking spaces and install traffic islands in connection with pedestrian crossings.

- Bus stops with platforms make it easier for bus passengers to cross the cycle track without coming into conflict with cyclists. Photo: Troels Andersen

Bus stops

Cycle tracks can increase the number of cycling accidents at bus stops if no precautionary safety measures are taken. Accidents with passengers getting off primarily occur where there is either a narrow platform or none, whereas accidents with passengers getting on occur at bus stops with a wide platform. Virtually all accidents between passengers getting off and cyclists occur at bus stops without platforms.

Studies of bus passengers and cyclists at bus stops without platforms show that when pedestrian crossings are installed, cycling speeds are significantly reduced when busses stop, and there are fewer serious conflicts between cyclists and bus passengers. Yield lines, rumble strips, and painted patterns at the bus stop do not have the same positive effect as a pedestrian crossing.

However, the road rules no longer permit pedestrian crossings across the cycle track at bus stops.

It’s a good idea to establish a stretch of standard cycle track (i.e. an elevated kerb between the cycle track and the pavement) at bus stops on roads with ridged cycle tracks.

Bus stops on roads with cycle tracks should be placed 20 m or more before the intersection. Otherwise stopping buses will reduce cyclist safety and make cyclists less visible to other road users. The bus stop should never be placed directly before the stop line at signalized intersections since waiting cyclists can block the way for bus passengers getting on or off the bus. The bus stop should preferably be placed after the intersection, which also has a positive effect on the bus’s accessibility.

- A bus bulb in the country where the cycle track leads around the bus platform. Photo: Troels Andersen

A bus platform should be at least 1.5 m wide and should have a different surface than the cycle track. Bus stops with many passengers getting on and off should have a 2.5 m wide bus platform to ensure that the platform doesn’t get too crowded, and that passengers with prams can get on and off safely.

Elderly pedestrians along Frederikssundsvej in Copenhagen experience getting on and off as the second most dangerous traffic situation. Around half the elderly that were questioned responded that they experience issues with cyclists at bus stops very often.

- If there is no bus platform a special bus stop surface can be applied to make the crossing point visible. Here concrete slabs were laid down on the cycle track at the bus stop. Photo Troels Andersen

A future scenario is an intelligent lighting system installed on the bus that activates a pedestrian crossing area across the cycle track, or activates the bus stop to create the crossing or platform.

Designing the start and termination of cycle tracks

The start and termination of a cycle track is an important part of the detailed project design. Ramps to and from the cycle track should form a gentle transition between the road and the track by continuing the cycle track surface without edges. Existing kerbs should be removed.

When the cycle track ends in mixed traffic, the traffic lane is widened by a 15-20 m long wedge shaped extension, and an edge lane is marked from the end of the cycle track to 15-20 m after the traffic lane extension. When a cycle track is continued as an edge lane or a cycle lane,f the traffic lane width should not be changed. Cyclists should be able to continue with no sideways change. When the cycle track ends abruptly drivers should be made aware of this by signage and a 1 m wide traffic island, which can forestall overtaking accidents.

Remember that wide bicycles and bicycle trailers also need to make turns from side roads. Odense and the City of Copenhagen paint cyclist approaches white so they’re easy to find.

Sources

Trafitec (2006): Effekter af cykelstier og cykelbaner.

Nielsen, Michael Aakjer; Olsen, Mette og Lund, Belinda la Cour (2000): Cyklisthastigheder i byområder,Notat 62, Vejdirektoratet, Danmark.

Søren Underlien Jensen, Trafitec (2006): Fodgængeres og cyklisters oplevede serviceniveau på vejstrækninger.

Vejdirektoratet (1992): Cykelstier i Frederiksborg Amt – En brugerundersøgelse.

Lahrmann, Harry (1992): Cykelbaner med asfaltvulst, Aalborg Universitet.

Herrstedt, Lene; Nielsen, Michael Aakjer; Ágústsson, Lárus; Krogsgaard, Karen Marie Lei; Jørgensen,

Else og Jørgensen, N.O. (1994): Cyklisters sikkerhed i byer, Rapport 10, Vejdirektoratet.

Københavns Kommune (1999): Frederikssundsvej – Evaluering af spørgeskemaundersøgelse, Udkast.