Anchoring the cycle track plan

The cycle track plan should involve citizens and organizations, and planners must constantly be on the lookout for opportunities for joining it with other construction projects. It is important that the plan links up with other objectives involving school routes, tourism and urban planning.

By Troels Andersen, Odense Municipality

A cycle track plan involves politicians, the general public, planners, and operations authorities, among others. In the final analysis the plan must receive political approval and is binding for the local authority either in the form of an action plan or by being written into the local authority’s master plan. The master plan, however, can only contain physical elements, such as tracks, tunnels, bridges and bicycle parking, but not signage, marking or campaign activities.

Citizens and organizations must be involved during the process, partly because they have personal knowledge of cyclist concerns and partly to ensure that the plan has a broad based anchor. Focus groups and workshops are useful for identifying challenges and possible solutions. A bicycle account, where citizen’s opinions are clearly voiced, can help promote a constructive debate.

In other words citizens should be involved in the process before the authority has definitively decided upon a plan. It is important to present the guiding principles and methods of prioritization openly. Citizen input can be used in budget negotiations and can motivate the different stakeholders (cable owners, operations personnel, etc.) to support the plan. The plan should include both infrastructure and other facilities (for example bicycle parking), as well as prioritization and funding of operations and maintenance.

It’s important to clearly establish the overall structure since many people are active in the process of changing road and cycle track systems. The cycle network plan is part of the foundation of a common understanding and cooperation within the local administration.

However, planners do not have all the necessary funds at their disposal to create a cycle network. The local authority being the road authority can require an in-depth analysis of different tasks and projects by which it might be possible to implement parts of the cycle network. An obvious example is to integrate the cycle track plan with the funding the road authority receives from independent, user financed, utilities organizations when reinstating local roads after cable roadworks. Establishing a cycle track with its own layout in connection with new construction of a natural gas pipeline may give a cost reduction of 50%, in reality cutting the price of the cycle track in half. However, that still leaves the other half, of course.

- A planner needs to be well acquainted with the project area. This is best done by inspection by bicycle. Here planners are agreeing that the shed needs to be torn down in order to establish a cycle link in Østerbro, Copenhagen .

It can be a good idea to calculate the estimated construction costs within the plan’s timeframe. Estimated co-financing from other sources can also be included. In Copenhagen the price of 1 km of cycle track can be twice as high as elsewhere in the country. When pricing concrete construction projects an actual cost price calculation needs to be carried out, i.e. an educated estimate based on measured volumes and updated unit prices. If there is a greater degree of uncertainty than normal the margin of uncertainty should be doubled – otherwise you run the risk of running out of money late in the game, and may have to cut out important portions of the project.

An objective prioritization based on an assessment of potential bicycle traffic, including school routes, places of education, private enterprises and cycle track network cohesiveness can be an excellent tool for prioritizing different projects. If a cycle track project means that a dangerous school route can become safe, this can save many of the school transport costs that are required by law. Naturally, regardless of the prioritization method there will always be a certain degree of local politics involved in the final political prioritization. Paths and school routes are often of great political interest.

A politically approved priority plan for implementing cycling infrastructure is often an extremely valuable tool in the daily work. It saves a lot of time in relation to citizen inquiries.

Is the plan cohesive?

When the administration draws up a cycling infrastructure plan, planners should discuss and assess whether it will be cohesive in practice:

- Does the cycling infrastructure connect residential areas and the main destinations of bicycle traffic, such as schools, and places of work and education?

- Are the routes direct?

- Is it easy to get to shops, sports facilities, amusements, and traffic terminals?

- Are the residential areas mutually linked so cyclists have practical shortcuts, and local cycle trips are faster than by car?

- Is there a structure where main routes have priority over side roads and local routes so they can attract most of the total bicycle traffic?

- Are there breakdowns of cohesiveness in the form of missing lighting, annoying barriers, too many traffic lights, or poor maintenance?

Minor breakdowns should be removed as quickly as possible as they reduce use of the cycle network. Larger breakdowns must be dealt with from a more long term perspective.

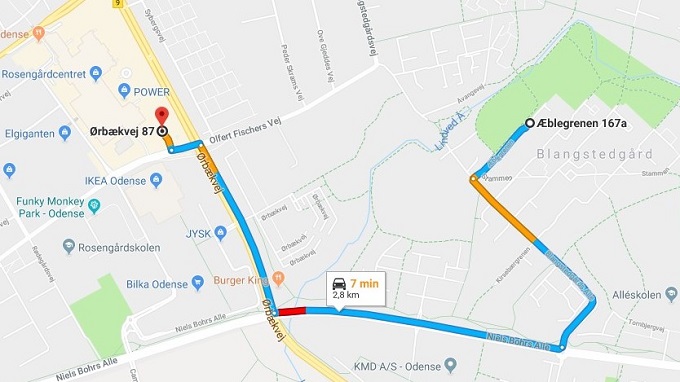

- An example in Odense, where a road closure for cars means the trip is half as long by bicycle, and actually even faster. Source: Google maps

Does the existing cycling infrastructure live up to the new construction standards? If not, a cycle track spot check should be carried out, especially at intersections. The structure of the individual intersection is often determined by when it was built, and the purpose of the spot check is to upgrade existing structures to a uniform, high standard. An actual cycle track inspection can be carried out.

Has thought been given to strong as well as weak cyclists? A direct route with heavy traffic may be acceptable for adult cyclists but not for school children. School children and their parents need to feel secure and may need an alternative school route to the main roads. School route plans should be coordinated with the cycle track plan.

Recreational cyclists and cycling tourists need to be offered attractive experiences and service.

If the initial infrastructure is occasionally below standard, has its later development been taken into account, so that signed routes may be upgraded to cycle lanes, which can then be upgraded to actual cycle tracks?

Is the mesh width appropriate in cycling infrastructure in urban areas? Often 400-500 m is sufficient, but in areas with many destinations, for example the city center, the mesh width can be smaller whereas in the more outlying areas it can be greater. In rural areas planners must make sure the proposed infrastructure leads to the main destinations, such as schools, workplaces, and service, and that attractive recreational destinations and accommodation can be reached securely and without difficulty. Does the plan give enough weight to additional cycle tracks with their own layout?

Are cycle tracks planned along roads with high speeds? It may be necessary to establish cycle tracks along such roads due to cyclist safety and sense of security. Perhaps the speed limit can be reduced until the cycle track system has been implemented.